Readings:

Song of Songs 1:1-8

Psalm 139:1–9

Jude 1-3

Mark 10:23-31

Preface of a Saint (1)

[Common of a Monastic or Professed Religious]

[Common of a Theologian and Teacher]

[Of the Incarnation]

PRAYER (traditional language)

O God, by whose grace thy servant Bernard of Clairvaux, kindled with the flame of thy love, became a burning and a shining light in thy church: Grant that we also may be aflame with the spirit of love and discipline and walk before thee as children of light; through Jesus Christ our Lord, who liveth and reigneth with thee and the Holy Ghost, one God, now and for ever. Amen.

PRAYER (contemporary language)

O God, by whose grace your servant Bernard of Clairvaux, kindled with the flame of your love, became a burning and a shining light in your church: Grant that we also may be aflame with the spirit of love and discipline and walk before you as children of light; through Jesus Christ our Lord, who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, now and for ever. Amen.

Lessons revised in Lesser Feast & Fasts 2024

Return to Lectionary Home Page

Webmaster: Charles Wohlers

Last updated: 10 July 2024

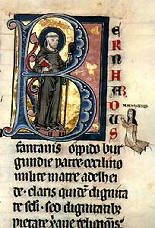

BERNARD OF CLAIRVAUX

ABBOT, THEOLOGIAN, AND POET (20 AUGUST 1153)

Bernard,

third son of a Burgundian nobleman, was born in 1090. His brothers were

trained as soldiers, but Bernard from youth was destined for scholarship.

One Christmas Eve as a child he had a dream about the infant Christ in the

manger; and the memory of it, and consequent devotion to the mystery of

the Word made flesh, remained with him throughout his life.

Bernard,

third son of a Burgundian nobleman, was born in 1090. His brothers were

trained as soldiers, but Bernard from youth was destined for scholarship.

One Christmas Eve as a child he had a dream about the infant Christ in the

manger; and the memory of it, and consequent devotion to the mystery of

the Word made flesh, remained with him throughout his life. Bernard had good prospects of success as a secular scholar, but he began to believe that he was called to the monastic life, and after a period of prayer for guidance, he decided at age 22 to enter the monastery of Citeaux (Latin Cistercium, appearing on modern maps as Corcelles-les-Citeaux), an offshoot of the Benedictines which had adopted a much stricter rule than theirs, and became the founding house of the Cistercian (Trappist) order. (Actually, the Trappists are a reformed (i.e. stricter) offshoot of the Cistercians, who are a stricter offshoot of the Benedictines.) He persuaded four of his brothers, one uncle, and 26 other men to join him. They were the first novices that Citeaux had had for several years. After three years, the abbot ordered Bernard to take twelve monks and found a new house at La Ferte. The first year was one of great hardship. They had no stores and lived chiefly on roots and barley bread. Bernard imposed such severe discipline that his monks became discouraged, but he realized his error and became more lenient. The reputation of the monastery, known as Clairvaux (48:09 N 4:47 E), spread across Europe. Many new monks joined it, and many persons wrote letters or came in person to seek spiritual advice. By the time of his death, 60 new monasteries of the Cistercian order were established under his direction.

For four years after 1130 Bernard was deeply involved with a disputed

papal election, championing the claims of Innocent II against his rival

Anacletus II. He travelled throughout France, Germany, and Italy mustering

support for his candidate (and, it should be added, preaching sermons denouncing

injustices done to Jews), and returned from one of these journeys with

Peter Bernard of Paganelli as a postulant for the monastery. The future

Pope Eugenius III spent the next year stoking the monastery fires. Years

later, Bernard wrote a major treatise of advice to Eugenius on the spiritual

temptations of spiritual power.

The papal election was not the only dispute in which

Bernard became involved. He was highly critical of Peter Abelard, one of

the most brilliant theologians of the day (see 21 April). Bernard believed

that Abelard was too rationalistic in his approach, and failed to allow

sufficiently for the element of mystery in the faith. When Abelard rejected

some of the ways of stating Christian doctrines to which Bernard was accustomed,

Bernard concluded, perhaps too hastily, that this was equivalent to rejecting

the doctrine itself. A conference was scheduled at Sens, where Abelard's

views were to be examined, but soon after it began Abelard decided that

he was not about to get a fair hearing, announced that he was appealing

to Rome, and left. He set out for Rome and got as far as Cluny, where he

stopped. Peter the Venerable, the abbot (see 30 April), was a friend of

both Abelard and Bernard, and managed to reconcile them before they died.

One

of Bernard's most influential acts, for better or worse, was his preaching

of the Second Crusade. The First Crusade had given the Christian forces

control of a few areas in Palestine, including the city of Edessa. When

Moslem forces captured Edessa, now called Urfa and located in eastern

Turkey) in 1144, King Louis VII of France (not to be confused with St.

Louis IX, also a Crusader, but more than a century later) was eager to

launch a crusade to retake Edessa and prevent a Moslem recapture of Jerusalem.

He asked Bernard for help, and Bernard refused. He then asked the Pope

to order Bernard to preach a Crusade. The pope gave the order, and Bernard

preached, with spectacular results. Whole villages were emptied of able-bodied

males as Bernard preached and his listeners vowed on the spot to head

for Palestine and defend the Sacred Shrines with their lives.

One

of Bernard's most influential acts, for better or worse, was his preaching

of the Second Crusade. The First Crusade had given the Christian forces

control of a few areas in Palestine, including the city of Edessa. When

Moslem forces captured Edessa, now called Urfa and located in eastern

Turkey) in 1144, King Louis VII of France (not to be confused with St.

Louis IX, also a Crusader, but more than a century later) was eager to

launch a crusade to retake Edessa and prevent a Moslem recapture of Jerusalem.

He asked Bernard for help, and Bernard refused. He then asked the Pope

to order Bernard to preach a Crusade. The pope gave the order, and Bernard

preached, with spectacular results. Whole villages were emptied of able-bodied

males as Bernard preached and his listeners vowed on the spot to head

for Palestine and defend the Sacred Shrines with their lives.

The preaching of the Crusade had an ugly side-effect.

In the Rhineland, a monk named Raoul wandered about telling crowds that

if they were going to fight for the faith, the logical first step was

to kill the Jews who were near at hand. There were anti-Jewish riots in

Mainz, (in the Rhineland), where the archbishop sheltered the Jews, or

many of them, in his palace, and sent an urgent message to Bernard to

come before both he and they were killed. Bernard came. He called Raoul

arrogant and without authority, a preacher of mad and heretical doctrines,

a liar and a murderer. Then he got nasty. Raoul sneaked off the scene,

and the riots were over. From that day to this, Bernard has been remembered

among Rhineland Jews and their descendants as an outstanding example of

a "righteous Gentile," and many of them (e.g. Bernard Baruch) bear his

name.

As for the Crusade, things went wrong from the start.

The various rulers leading the movement were distrustful of one another

and not disposed to work together. Of the soldiers who set out (contemporary

estimates vary from 100,000 to 1,500,000), most died of disease and starvation

before reaching their goal, and most of the remainder were killed or captured

soon after their arrival. The impact on Bernard was devastating, and so

was the impact on Europe. In 1153, Bernard journeyed to reconcile the

warring provinces Metz and Lorraine. He persuaded them to peace and to

an agreement drawn up under his mediation, and then, in failing health,

returned home to die.

If Bernard in controversy was fierce and not always fair, it was partly because he was a man of intense feeling and dedication, quick to respond to any real or supposed threat to what he held sacred. It is his devotional writings, not his polemical ones, that are still read today. Among the hymns attributed to him are the Latin originals of "O Sacred Head, sore wounded," "Jesus, the very thought of Thee," "O Jesus, joy of loving hearts," "Wide open are Thy hands (to pay with more than gold the awful debt of guilt and sin, forever and of old--see the Lutheran Book of Worship et alibi)," and "O Jesus, King most wonderful." His sermons on the Song of Songs, treated as an allegory of the love of Christ, are his best-known long work.

by James Kiefer