Readings:

1 Kings 19:9-18

Psalm 27:5-11

1 John 4:7-12

John 17:6-11Preface of a Saint (2)

[Common of a Monastic or Professed Religious]

[Common of a Pastor]

[Common of a Theologian and Teacher]

[Of the Incarnation]

PRAYER (traditional language)

Gracious God, who didst kindle in thy servants Richard Meux Benson and Charles Gore the grace to lead a revival of monastic life: Grant us also the resolve to serve thee faithfully in contemplation and prayer, ministering to the world that thou hast made, through Jesus Christ our Lord, who liveth and reigneth with thee and the Holy Ghost, ever one God, in glory everlasting. Amen.

PRAYER (contemporary language)

Gracious God, who kindled in your servants Richard Meux Benson and Charles Gore the grace to lead a revival of monastic life: Grant us also the resolve to serve you faithfully in contemplation and prayer, ministering to the world that you have made, through Jesus Christ our Lord, who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, ever one God, in glory everlasting. Amen.

Lessons revised at General Convention 2024.

Return to Lectionary Home Page

Webmaster: Charles Wohlers

Last updated: 16 November 2024

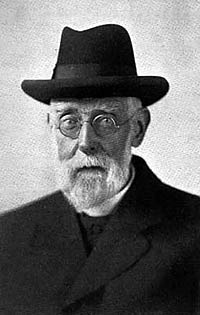

RICHARD

MEUX BENSON

RELIGIOUS, 1915

AND

CHARLES GOREBISHOP OF WORCESTER, BIRMINGHAM & OXFORD, 1932

Born into a wealthy family of London in 1824, Benson was taught at home by a private tutor and entered Christ Church, Oxford. After his degree and ordination and a curacy at Surbiton, in 1850 he became vicar of Cowley, Oxford. He was considered High Church. In 1858 Benson conducted a retreat for priests using material taken in part from the Spiritual Exercises of Ignatius of Loyola. In 1859, having erected a new parish church dedicated to St. John the Evangelist, Benson planned a mission to India but abandoned the plan at the request of his bishop.

At the time there were convents of Anglican women in England, and in 1865 two priests joined Benson in Cowley to begin community life under the name of Mission Priests of St. John the Evangelist with Benson as Superior.

The form of religious life instituted by Benson was not purely contemplative — its members engaged in active external ministry — but they recited the Divine Office together daily in choir, and Benson emphasized contemplation. The brothers were to get an hour's meditation daily if possible, and he gave the community a summer retreat of four weeks, later reduced to fortnight. He prescribed other retreat days and silence days. As a religious founder, he concentrated on essentials, among which he reckoned life-vows, taken with precautions as to maturity; regular confession; choir office, prayer and meditation; and priestly ministry. He fully recognized the authority of his bishop over the priests of the community, who were clergy of the diocese, but not as extending to their private life together.

From 1870 to 1883 the Society spread to the United States, India, and South Africa. Benson himself made an American mission tour. In 1884 the society adopted a Constitution and Rule drafted by Benson.

During the creation of the Society, Benson had maintained his duties as a parish vicar. In 1886 he resigned this charge to devote all his attention to the Society and its mission.

In 1890 Benson stepped aside for another to be elected Superior. He spent one year in India, and eight years at the American house in Boston.

The last sixteen years of Benson's life were lived at home again. He celebrated the Holy Eucharist as long as he could stand at the altar, and then was wheeled in a chair to his Communion every morning. He died on January 14, 1915.

from Wikipedia

More information on Richard Benson is available from Project Canterbury.

Gore attended Harrow Prep School (during which time he became dedicated to weekly Communion), and Balliol College, Oxford (where he became a supporter of the trades-union movement). He took First Class Honors in Classical Moderations and in Greats (philosophy), and was elected a Fellow of Trinity in 1875. He was ordained to the priesthood in 1878. In 1880 he became Vice-Principal of Cuddesdon Theological College, founded by Edward King. During the three years he spent there he did a great deal of outside preaching and lecturing. After the death of Edward Pusey, a library and study center was established at Oxford in 1883, known as Pusey House, and Gore became its first Principal, a position he held until 1893. His appointment raised some eyebrows, since Gore was known to be friendly to what was called the Higher Criticism, which favored non-traditional views on the authorship of some books of the Old Testament (Lower Criticism means attempting to establish the original text of the Scriptures by diligently comparing the existing copies and analyzing their variations), while Pusey had firmly opposed the Higher Criticism.

In 1888 Gore wrote The Ministry of the Catholic Church (or The Church and the Ministry — my sources differ), a book on the origins of the Christian Ministry and its development in the first two centuries of the Christian era. In the same year, he wrote Roman Catholic Claims, a reply to assertions that the Anglican Church was not the true successor of the New Testament Church. In 1889, he helped to found the Christian Social Union (he was one of the two Vice-Presidents), dedicated to promoting the view that Christian principles as applied to the political and economic organization of society demanded reform along trade-unionist and moderate socialist lines. His political views aroused some public protest.

Considerably more protest was aroused, however, by the publication, also in 1889, of a book called Lux Mundi (meaning "Light of the World"): A Series of Studies in the Religion of the Incarnation. The book was a set of essays by various writers. Gore was the general editor, and contributed one essay. Overall, the book expressed the belief of many educated Christians that Biblical and archaeological studies and scientific discoveries had made it necessary for the Church to re-examine and perhaps restate some of its traditional formulations. The book was a sensation, and considered by many to be less a restatement than an abandonment of traditional doctrines. Gore's essay was called, "On the Inspiration of Holy Scripture." He distinguished sharply between the Old and New Testaments, saying that the New Testament accounts were either eye-witness or close to eye-witness accounts of the events described, while we had reason to suppose that some Old Testament accounts were written centuries after the event, and were not reliable sources of factual detail. Their value is not as a revelation of historical of scientific information, but as a revelation of God's nature and His dealings with us. Thus, the point of the story of Adam and Eve is not that the human race is less than ten thousand years old, but that obedience to God makes men happy, and disobedience to God makes them unhappy. Gore wrote: "It is of the essence of the New Testament, as the religion of the Incarnation, to be final and catholic: on the other hand, it is of the essence of the Old Testament to be imperfect, because it represents a gradual process of education by which man was lifted out of the depth of sin and ignorance." Some objected: "But you are on a slippery slope! If Genesis is not reliable history, how can we be sure of later books?" To this, Gore might have replied: "Consider the history of ancient Rome. The history begins with stories about the flight of Aeneas from Troy, and continues with Romulus and Remus, and with the story of Lucretia, and Horatius at the bridge, and Mucius Scaevola thrusting his hand into the fire, and the secession of the plebs, and the treason of Tarpeia, and Curtius leaping into the abyss, and so on. Yet the same books that tell us these stories about early Rome also tell us about the First and Second Triumvirates, and the battle of Actium, and so on. No one says that, if we reject the story of Dido and Aeneas as legend, we cannot trust the later accounts as history."

What chiefly outraged Gore's critics, however, was his adoption of what is called the Kenotic Theory of the Incarnation. The Greek word Kenosis means "emptying," and is used in Philippians 2:7, where we read that Jesus,

+ having the nature of God,

+ did not count equality with God a thing to be grasped,

+ but emptied himself, and took the nature of a servant.

Gore put forward the suggestion that Jesus, when He took upon Himself the limitations of our human nature, accepted the limitations of human knowledge, and that therefore, when He spoke (for example) of the Flood, He was simply accepting the common assumptions of His culture, and we are not bound to accept these assumptions as correct.

Not surprisingly, many readers found this view completely unacceptable. The book was widely read and disputed over, and cheap, popular editions were soon available.

Two years later, Gore was invited to deliver the annual Bampton Lecture Series. He welcomed the opportunity to make clarify his position and reassure his listeners of his fundamental orthodoxy. The Lectures were delivered in Lent, 1891, in the University Church of Oxford, St. Mary the Virgin, to capacity audiences. Listeners filled the pews, stood in the aisles, and sat on the steps of the chancel and the pulpit. A few months later, the lectures were published in book form as The Incarnation of the Son of God.

Earlier, in 1887, Gore had founded the Society of the Resurrection, an association for priests, aimed at a deepening of the spiritual life. In July 1892 this became the Community of the Resurrection, a religious order for priests, beginning with six members. The members declared their intention of remaining celibate for life, but took vows of celibacy for only one year at a time, rather than taking a vow binding for life. (In technical language, they were monastics of the Simple Profession rather than of the Solemn Profession.) The Community first lived at Pusey House, but soon (1893) moved to Radley, near Oxford, and in 1898 to its present headquarters in Mirfield, Yorkshire. Many Americans (and perhaps others) will know the Community best through the work in the 1950's and early 1960's of the priest Trevor Huddleston, author of Nought For Your Comfort, a book discussing racial animosities and inequities in the Republic of South Africa and elsewhere, and calling Christians to a ministry of justice and reconciliation.

Gore, while retaining his office as Senior of the Community of the Resurrection, was made a canon of Westminster late in 1894, where his preaching attracted great crowds. When it was known that he was scheduled to preach, would-be listeners gathered outside the Abbey well in advance, and when the doors were opened the building filled like a lock in flood-time. In minutes, not even standing-room was to be found. In addition to his Sunday sermons, he also gave weekday lectures, many of them later collected into books, such as The Sermon On the Mount (1896), The Epistle To The Ephesians (1897), and The Epistle To the Romans (1898). In 1901 he wrote The Body of Christ, dealing with the Sacrament of the Lord's Supper, asserting and defending the doctrine that Christ is objectively present in the Sacrament, and that the Sacrament is a sacrificial offering, but repudiating certain late mediaeval innovations in worship, such as Processions of the Sacrament, unknown to the Primitive Church.

As tension increased between the British government and the Boer republics of South Africa, Gore denounced British Imperialism, and when war began in 1899 he denounced the British policy of rounding up Boer civilians in detention camps, where the mortality rate was very high. He wrote a fierce letter on the subject to The Times. The next day, there was a fierce reply by a canon of Worcester (pronounced "Wooster") Cathedral. The Worcester area was the political base of Joseph Chamberlain, the Colonial Secretary whose policy Gore was denouncing. A few days later, Gore was appointed Bishop of Worcester. He was consecrated in February 1902. The diocese included the city of Birmingham, which had been tiny or non-existent when the dioceses of England were organized, but which had grown to become a large industrial city. Gore saw that the needs of Birmingham and of the surrounding rural areas were quite different, and immediately began to urge a division. Chamberlain, who had come to respect and admire Gore, helped steer the necessary legislation through Parliament. In 1905 Birmingham was organized as a separate bishopric and Gore became its first bishop. Things went well for him there. Under his leadership, church attendance increased considerably, new buildings were erected, and many priests brought into the diocese to minster to the growing congregations. In spite of his adherence to views widely regarded as tending toward Roman Catholicism, he established strong bonds of courtesy and affection with the Protestants of Birmingham.

In 1911 he was transferred and became Bishop of Oxford instead. This was a sprawling, largely rural diocese, but Gore traveled about, regularly visiting the parishes under his care, and on most Sundays preached in at least two different pulpits. Since college days he had been committed to educational and economic improvement for the working class, and he gave an annual lecture to the Workers' Educational Association at Reading. In 1911 a major labor dispute arose in Reading, and Gore publicly sided with the workers, giving them money, and pressing for a panel of inquiry into the living conditions of the workers. The report of the panel favored the workers' cause, and won for Gore a great deal of gratitude and affection among working-class people in his diocese and elsewhere.

In the next few years, several Anglican clergy publicly declared that an Anglican might reasonably deny the Virgin Birth and the physical Resurrection of Christ and remain an Anglican. Gore was horrified, and proposed to resign his bishopric so as to devote himself to contending against a position that he believed to be destructive of all Christian faith. His friends persuaded him to reconsider.

In 1914, WWI broke out. Gore dutifully travelled to France twice to preach and administer the sacraments to men in uniform. In June 1918 he went to the United States to speak on the Church and the post-war world. He spoke in New York, Washington, Chicago, Cleveland, various cities in Tennessee, Georgia, and Alabama, then on to Milwaukee, Nashotah, Detroit, Boston, Washington, Philadelphia, Baltimore, New York, and then back to England as the war ended in November. He spoke chiefly on reconciliation and the necessity, once the war had been won, of restoring Germany as soon as possible to the family of nations.

After the war, Gore resigned his bishopric and retired in July 1919, being 66 years old. He was flooded with invitations to speak or preach, and had a supply of postcards printed reading, "Sorry, Can't. C.G." for immediate response to most of them. The invitations he did accept were quite enough to fill his calendar. Later that year he became a lecturer in theology at King's College, and was made a Life Governor. From 1924 to 1928 he was Dean of the Faculty of Theology in the University of London. He also served on the Council of Christian Ministers on Social Questions, the Christian Social Crusade, the Industrial Christian Fellowship, the General Council of the League of Nations, the Oxford Mission to Calcutta, the Universities' Mission to Central Africa, the Board of Governors of Pusey House, the World Conference on Faith and Order (of the World Council of Churches), and the Archbishop's Eastern Churches Committee. Not bad for a man in "retirement."

During these years he also completed his Exposition of the Epistles of Saint John (1920), and then wrote his trilogy, Belief in God (1921), Belief in Christ (1922), and The Holy Spirit and the Church (1924). These three works were re-issued in a single volume called The Reconstruction of Belief, intended as an exposition and defense of the faith of the Catholic Church, as stated in the Holy Scriptures and codified in the Councils of the first five centuries of the Christian era, and now restated in modern terms--"the faith once delivered to the saints presented in conformity with twentieth-century categories of thought and scientific methods of reasoning." [Rice] The book prompted many objections, chiefly from Modernists, and Gore dealt with many of these objections in a sequel called Can We Then Believe? In 1928 the SPCK (Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge) published A New Commentary On Holy Scripture, which contained notes on every book of the Old and New Testaments and of the Apocrypha, together with many general articles. Gore was the general editor. Gore also wrote Christ and Society (1928), dealing with the social and economic applications of Christian ethics; Jesus of Nazareth(1929), dealing with the person and work of Jesus; and The Philosophy of the Good Life (1930), the Gifford Lectures, dealing with answers offered by various philosophies and religions to the question, "How ought I to live?" (The Gifford Lectures are lectures in Natural Theology, in which the lecturer is barred from asking his listeners to accept the authenticity of any revelation. Perhaps the best-known Gifford Lectures are William James's The Varieties of Religious Experience.) Gore's last book, Reflections On the Litany, was published the day after he died.

In November of 1930, he began a six-month tour of India, preaching and lecturing pretty much in every district in the country, "speaking whenever he was not walking, riding, or sleeping." He returned home totally exhausted. From then on his health deteriorated. In January 1932 he acquired a severe cough, and then pneumonia. On Friday 15 he was still able to write a few postcards to friends. Then he fell into a coma, and died on the morning of Sunday 17 January 1932. His influence remains great.

[Note: This Bio is based largely on the book The Bridge Builders: Biographical Studies in the History of Anglicanism, by Hugh A. Lawrence Rice (1961, Darton, Longman & Todd, London; Longmans, Green & Co, New York).]

by James Kiefer

More information and links to many of his works are available from Project Canterbury.